Sally Kempton’s Awakening Shakti: The Transformative Power of the Goddesses of Yoga serves to provide a deeper understanding of and appreciation for the various goddesses associated with Tantric Narrative. While familiar with each of the goddesses covered due to the dharma talks during various trainings with Janet, this text not only elaborated on those teachings but also illuminated each goddess in form and function.

With each chapter dedicated to a goddess, Kempton details the stories associated with her, how to approach the goddess, how to ask for help, how the goddess is revealed, characteristics of the goddess (including the shadow side), and concludes with mantras. What was particularly illuminating was Kempton’s application of the goddess in everyday life involving ordinary people; thus bringing into view each goddess through a contemporary lens that offers a very modern and realistic perspective. In fact, on numerous occasions while reading, I found myself reflecting on situations and events that revealed my own connections with each deity.

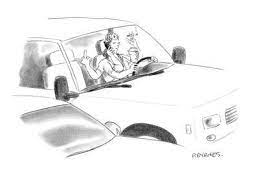

Kempton’s description of a cartoon she had seen in the New Yorker featuring Durga made me laugh, but on the other hand, it also really resonated with me. I had to find it!

As a mother and retired educator, the personality of Durga is evident in me, “When you feel drawn to this goddess, it usually indicates one of two things: either you need an infusion of Durga-like strength, or you carry the Durga archetype as part of your personality . . . . warrior-style leadership.” (68). Juggling a high pressure job and domestic life, I was the epitome of a multi-tasker (oftentimes to my own detriment). By day, I was a high school teacher with 2-3 different courses to plan, teaching 5-6 periods a day, and attempting to empower classrooms full of struggling, impoverished adolescents. By night, I was a mother and wife – two roles of which I am very protective. The shadow side of Durga is her need for “control to the level of micromanagement”, but this applies only to myself as it manifests in my OCD as a result of the “relentless inner critic” highlighting every one of my faults and flaws (72). According to Kempton, “[o]ne way to get a felt sense of the Durga Shakti is to remember a moment when you recognized, from the deepest place inside of you, that something was wrong, that it had to change.” (73). This moment for me was when my son was 2-years old: my father had passed from Non Hodgkin’s Lymphoma associated with Agent Orange exposure in Vietnam; my mother was undergoing chemotherapy for breast cancer; and my son had entered the “terrible twos”. As a result of a particular moment when my frustrations and anger were beyond my control, I saw myself turning into my mother. It scared me. I had to make a change. Thus, I found refuge in a local yoga studio and discovered a path towards revealing and healing.

Lakshmi’s qualities of “generosity, loving-kindness, carefulness, unselfishness, gratitude . . . discipline, cleanliness, and order” also resonate with me to the point of imbalance (106-107). I will often make sacrifices for others to the detriment of my own time, resources, energy, etc. However, since retiring from public education, I’ve been able to find more balance in my daily life (to include keeping a tighter budget). While reading the chapter on Lakshmi, I took pause, “In India, the yearly Lakshmi festival begins with a thorough house cleaning. Everything in the house is scrubbed and polished, and only when the dust and first have been removed is the household considered ready to welcome Lakshmi.” (109). Before reading this particular chapter, I had taken advantage of my husband, son, and dog being gone for a week; to create balance, I focused on deep cleaning and polishing one room of the house at a time over the course of the week. Coincidence? Or prophetic?

Kempton’s exercise “Dialoguing with Kali” outlines writing down questions for Kali with your dominant hand (for me, right) and then writing the answers with your nondominant hand. This immediately reminded me of a similar application to my own practice. Over the past few years, Ida and Pingala nadis have really transformed my practice and my teachings. I began with longer holds on the left side during yin and restorative classes; and a couple of weeks ago, I began my cueing the left side first as opposed to the right – much to the confusion of all. Kali also surfaced in a recent event at a local Starbucks. After a yoga class, a long time friend and I decided to stop for a coffee. While we were conversing and regaling in laughter, another patron began yelling at us, “Can you quiet down. No one here is interested.” Kali’s fire indeed, “[Sometimes] the way through Kali’s fire is utter surrender . . . sometimes, it’s quite simply our ability to love her even in her terrible form.” (140). While my friend wanted to yell back, I discouraged him by simply saying, “The holidays are tough for some people.”

In Part One: Receiving the Energy of Parvati, I was reminded of a memorable moment during aarti at our New Year’s Eve Puja in India that, even now, brings tears to my eyes. After a round of Bhakti, Janet circulated to perform tilaka (the application of the kumkum powder). When she knelt down before me, and our eyes met, I was overcome with emotion, “Parvati’s strong and tender love-light now illuminates your heart, purifying it of wounds and blocks, dispelling the armor that you’ve erected around it. As your heart opens and releases its blocks, tears might come. Let them flow.” (162). During this dramatic pause in time and space, I acknowledged the divineness that resides deep within her as well as within myself.

According to Kempton, “[w]hen words flow easily, when ideas come up out of nowhere, when you say something so powerful and profound that it surprises even you, you are experiencing Saraswati” (178). This happens often as I guide classes to create sacred space by which to begin or to end one’s practice. The wealth of knowledge I have gained since beginning my training with Janet has been held, permeated my heart and mind to the point that it has become a part of me and has led me to express things in my own words in unique ways (187). I have experienced her “creative flow through language, speech, and sound” on numerous occasions, particularly in mantra or Bhakti (179). Singing has always come naturally to me. I remember the first class I ever took with Janet at the Midwest Yoga Conference; I never felt more alive and empowered through the Bhakti she offered. Like Saraswati, I enjoy “solving intellectual and artistic problems, discovering connections and new paradigms” (179). As a public educator, students always were amazed at how I was able to empower them by asking “the right question – the question that elicits a new way of thinking or a different way to look at a problem.” (180). Like Saraswati, I am “a proof-reader, a timekeeper, a perfectionist.” (191). I also connect with her in what Kempton states is “arousal from below.” (195). All through college, writing was the “process of regurgitating it onto paper, resisting the urge to edit . . . Later to . . . sculpt the mess of words” into a well-written essay (192). After all the writing and research, the moment I walked away, the inspiration arrives (195). As for her shadow side, this too rings true for me as “negative self-talk all linger in the heart . . . the brain is wired to remember the negative much more easily than the positive.” (182). But I am continuing the work necessary to change the narrative.

While additional deities were also included in this text, the foregoing were the ones that truly resonated with me in one way or another. I would definitely recommend it to those interested in delving deeper into Tantra.

Work Cited:

Kempton, Sally. Awakening Shakti: The Transformative Power of the Goddesses of Yoga. Sounds True, 2013.

Nicolai Bachman’s

Nicolai Bachman’s  Each chapter covers a key concept, along with a relevant quote, analysis, thoughts and exercises for the practitioner. The author applies the principle to various modern examples and experiences, thus making it more accessible to the reader. For example, in Chapter 31 titled “Asteya” Bachman states, “If we interrupt someone during a conversation, we steal their right to be heard.” (154). According to Bachman, “The philosophy of yoga so eloquently written in these

Each chapter covers a key concept, along with a relevant quote, analysis, thoughts and exercises for the practitioner. The author applies the principle to various modern examples and experiences, thus making it more accessible to the reader. For example, in Chapter 31 titled “Asteya” Bachman states, “If we interrupt someone during a conversation, we steal their right to be heard.” (154). According to Bachman, “The philosophy of yoga so eloquently written in these

tone’s text titled

tone’s text titled

Michael Stone’s text titled

Michael Stone’s text titled