“Lord Ram gave Hanuman a quizzical look and said, “What are you, a monkey or a man?” Hanuman bowed his head reverently, folded his hands and said, “When I do not know who I am, I serve You and when I do know who I am, You and I are One.” ― Tulsidas, Sri Ramcharitmanas

“Lord Ram gave Hanuman a quizzical look and said, “What are you, a monkey or a man?” Hanuman bowed his head reverently, folded his hands and said, “When I do not know who I am, I serve You and when I do know who I am, You and I are One.” ― Tulsidas, Sri Ramcharitmanas

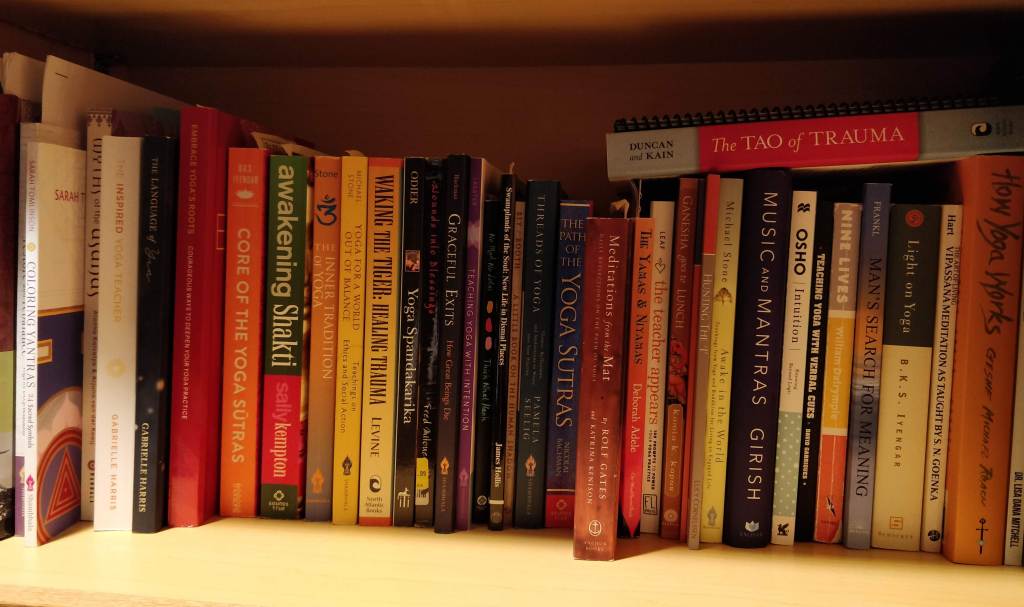

This quote is reminiscent of the closing dharmā talk for “Living the 8-Limbs” training with Janet. Indeed, it has been a journey to the self through the self on many levels. Since beginning my training with Janet in 2016, I have discovered much about myself and have been able to embed a lot of the teachings in my own practice as well as incorporate them into my teachings. Throughout this particular training, I found myself spending a great deal of time with each module, some more than others. I was also blessed to have witnessed and experienced the first and second limbs in action while in India. In the end, I have much work to do, but the journey of unpacking continues with more awareness.

First Limb: The Yāmas

First Limb: The Yāmas

The first limb entails The Yāmas that provide guidance with regards to ethical practices through the use of restraints.

Ahiṃsā, the first of the yāmas, dictates nonviolence and compassion. According to Nicolai Bachman in The Path of the Yoga Sutras, “By law of cause and effect, every action has a consequence” (144). Commonly referred to as karma, “I alone am responsible for my thoughts, words, and actions” (147). Indeed, what you put out into the universe comes back to you. The various triggers that may move one towards violence and/or non-compassion include feelings of fear, imbalance, powerlessness, and self-loathing. Deborah Adele in The Yamas & Niyamas makes a very clear distinction with regards to fear, “We need to know the difference between the fears that keep us alive and the fears that keep us from living.” (23), Much of my deeply rooted fears and feelings of powerlessness stem from my traumatic upbringing. However, it also manifests itself in how I am towards others. According to Adele, “When we try to take someone out of their challenge or suffering, we take them out of the environment that offers them a rich learning experience” (34). There is definitely a fine line between helping and hindering, and I have to remember that my personal experiences are not those of others.

The second yāma, Satyā, is based on truthfulness and sincerity. Adele states, “There is profound courage to this kind of willingness to be raw with reality as it is, rather than to run from it or construct a barrier to soften it.” (54). The triggers that may cause one to lie, either to one’s self or to others, include: the need to protect one’s ego, to create a sense of belonging, or to assuage one’s fear of loss. For me, after a childhood preconditioned towards self-preservation and survival, it has been quite the battle to focus on the reality of the present moment. While I still waiver into preconditioning on occasion, I am better able to recognize it and take a step back: am I trying to protect myself? Am I trying to belong? What am I afraid to lose? Afterall, “To be a bold person of truth is to constantly look for what we are not seeing and to expose ourselves to different views than the ones we hold sacred.” (51).

“The victories of truth have never been won without risks” – Gandhi.

Astēya, the third of the yāmas, involves non-stealing from others. While at first it appears like an obvious commandment “thou shall not steal” it actually goes beyond to include the moments and experiences of others. For example, “If we interrupt someone during a conversation, we steal their right to be heard.” (Bachman, 154, 163). Being solutions-oriented with a wide range of experiences, I often have to stop myself from offering my own personal experience, suggestions, feedback, and opinions. Over time, I have learned that life struggles are not always a bad thing: “Often we mistake these tasks as a burden rather than an opportunity to grow our compassion and skill level.” (Adele, 72). However, my life struggles are mine alone and do not necessarily apply to others. Over the years, I have been working on actively listening and allowing others the opportunity to process. In this sense, “Receiving is giving as well.” (Bachman, 155). Adele takes it further and on a personal level for me, “All self-sabotage, lack of belief in ourselves, low self-esteem, judgements, criticisms, and demands for perfection are forms of self-abuse in which we destroy the very essence of our vitality.” (66). My being a perfectionist with low self-esteem manifests in my need to be useful and helpful.

Astēya, the third of the yāmas, involves non-stealing from others. While at first it appears like an obvious commandment “thou shall not steal” it actually goes beyond to include the moments and experiences of others. For example, “If we interrupt someone during a conversation, we steal their right to be heard.” (Bachman, 154, 163). Being solutions-oriented with a wide range of experiences, I often have to stop myself from offering my own personal experience, suggestions, feedback, and opinions. Over time, I have learned that life struggles are not always a bad thing: “Often we mistake these tasks as a burden rather than an opportunity to grow our compassion and skill level.” (Adele, 72). However, my life struggles are mine alone and do not necessarily apply to others. Over the years, I have been working on actively listening and allowing others the opportunity to process. In this sense, “Receiving is giving as well.” (Bachman, 155). Adele takes it further and on a personal level for me, “All self-sabotage, lack of belief in ourselves, low self-esteem, judgements, criticisms, and demands for perfection are forms of self-abuse in which we destroy the very essence of our vitality.” (66). My being a perfectionist with low self-esteem manifests in my need to be useful and helpful.

The fourth yāma, Brahmacharya, concerns the conservation of vital energy and advocates non-excess. According to Bachman, “Throughout life, it involves control, moderation, pacing ourselves, and maintaining our inner orientation” (158). However, on a deeper level, Adele states “Practicing non-excess preserves and honors this life force within us, so that we can live with clarity and sacredness” (81). Feelings that might trigger excess or wasting of energies include feelings of avoidance, denial, isolation, and insignificance. As a mother and professional educator, I often struggle with balance between my work and personal lives. I often sacrifice my own practice and well-being for the sake of others. Additionally, when feelings of insignificance arise, I devote more energy towards those areas in my life in which those feelings reside. Now that I am more aware of these tendencies, I am in the process of finding more balance.

“We begin to see the sacred in the ordinary and the ordinary in the sacred.” (Adele, 82).

Aparigraha, the final yāma, concerns non-hoarding. I found myself reflecting on this yāma more than the others probably because it is the one I struggle with the most. My “hoarding” is not of the material nature, but more about who I am in relation to my past. For most of my life, I have embraced my past as contributing to the person I am today: a survivor, strong, compassionate, and courageous. While I understand the nature of impermanence, I continue to find myself grasping to this identity. According to Adele, “Subtle attachments come in the form of our images and beliefs about ourselves.” (95). Despite my traumatic upbringing, I have done very well to persevere. However, how does the “story” continue to serve me? In what way does it continue to define me? Why am I so attached to it? Clearly, I have to find a way to let go of the past, for “Letting go of the ownership opens us up to full engagement with what is set before us in the present moment.” (98). Since my abuser passed several years ago, I have been able to let go of the story a little bit at a time.

Second Limb: The Niyāmas

Second Limb: The Niyāmas

The second limb entails The Niyāmas that provide guidance with regards to one’s personal self-care.

The first of the niyāmas is Saucha, cleanliness of “our bodies, our thoughts and our words” (105). According to Adele, “Cleanliness is a process of scrubbing the outside of us; it changes our outer appearance. Purification works on our insides and changes our very essence.” (109). However, she further clarifies, “Purity is not our attempt to make something different than it is, rather it is to be pure in our relationship with it, as it is in the moment.” (109). Again, the emphasis is on the present moment. Personally, it also reminds me of my need to control, especially when my reality is beyond my control. This typically manifests itself through my “perfectionism” in my immediate environment. Over the years, I have been “stepping back into a quiet space, regrouping our thoughts, updating our to-do list, and organizing our workspace in order to calm the heart-mind and reduce stress and anxiety” (Bachman, 76). As a result, I have become far less reactive, but again, there are moments in which my control waivers.

“I enter fully into each experience, / and I come out fully from each of them, too. / I put the whole of me into all I do, / and . . . out of all I do.” – Krishnamurti

Santoṣā, contentment and gratitude, is the second niyāma – it “is being grateful for what we have and content with who we are and where we are in life.” (Bachman, 179). I was first introduced to this niyāma during the 5-Elements training in Mexico, 2016. Since the training, each and every one of my practices incorporates moments of gratitude. However, while I have immense gratitude, I also struggle with attachment in my practice as well as in my teaching. According to Bachman, “One aspect of contentment is being unattached to the results of our actions” (181). Adele pinpoints this succinctly, it “invites us into contentment by taking refuge in a calm center, opening our hearts in gratitude for what we do have, and practicing the paradox of ‘not seeking’” (120). Feelings of complacency, regret, and seeking happiness have kept me from finding balance. However, I am gradually becoming more aware of staying present, because “There is nothing more that can or does exist than this very moment.” (122).

Kriyā-Yoga

The last three niyāmas are grouped to form Kriyā-Yoga: Tāpas, Svādhyāya, and Iśvara-Praṇidhāna. Collectively, they create a practice in action in which “to weaken our mental-emotional afflictions (kleśas), and cultiplate complete attention (samādhi).” (Bachman, 186).

Tāpas, the third of the niyāmas, relates to one’s physical practice that serves to cause positive change. According to Bachman, “Tapas creates heat and thus change” (190). Indeed, if it doesn’t challenge you, it won’t change you, thus “Change is necessary for progress to occur” (191). Since beginning a regular yoga practice over 14 years ago, what began as an ego-driven practice slowly evolved into a more mindful practice. There are instances in my own practice in which I challenge myself: holding a particular posture or attempting a posture in which I am laden with fear. Can I breath through it? Can I let it go if I don’t succeed? Can I do it without need or desire? Can I find balance between effort and effortlessness? Can I find comfort in discomfort? Indeed, Adele’s question encapsulates this inner dialogue, “Can we grow our ability to stay in the fire and let ourselves be burned until we are blessed by the very thing that is causing us the pain and suffering?” (141). Afterwards, it has been instrumental in my everyday life, particularly in those instances of crisis: “The promise of a crisis is that it will pick us up and deposit us on the other side of something.” (143). While I continue to have moments in which I want to “fight” or “flee”, my reaction has softened and become more mindful.

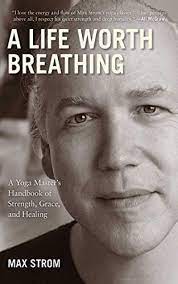

The fourth niyāma, Svādhyāya, is the study by and of one’s self. This niyāma was initially introduced to me during the Energetic Alignment and Intuitive Sequencing trainings. As stated earlier, the past few years have been an intense self-study for me. One of the required readings, Peter Levine’s Waking the Tiger: Healing Trauma was key in understanding the effects of my pre-conditioning. According to Bachman, “Self-observation gives us the power to convert old, harmful behavior into new, helpful action” (197-98). It is definitely a process of revealing the many “boxes” that constrain me (Adele, 149). These revelations have occurred throughout my practices and various trainings, thus making me more aware: “The witness is our ability to watch ourselves act and respond. It is our ability to watch our thoughts and our emotional disturbances . . . . The witness is our ability to watch the ego rather than identify with it.” (159). Not only does every single practice begin and end in stillness to observe, but I catch myself pausing throughout my day to simply observe and to witness. According to Adele, “self-study is about knowing our true identity as Divine and understanding the boxes we are wrapped in. This process of knowing ourselves, and the boxes that adorn us, creates a pathway to freedom.” (149). For me, Bhaktī reveals qualities that I have either discovered within myself or am still seeking to find, afterall, “We are, at the core, divine consciousness.” (149).

The fourth niyāma, Svādhyāya, is the study by and of one’s self. This niyāma was initially introduced to me during the Energetic Alignment and Intuitive Sequencing trainings. As stated earlier, the past few years have been an intense self-study for me. One of the required readings, Peter Levine’s Waking the Tiger: Healing Trauma was key in understanding the effects of my pre-conditioning. According to Bachman, “Self-observation gives us the power to convert old, harmful behavior into new, helpful action” (197-98). It is definitely a process of revealing the many “boxes” that constrain me (Adele, 149). These revelations have occurred throughout my practices and various trainings, thus making me more aware: “The witness is our ability to watch ourselves act and respond. It is our ability to watch our thoughts and our emotional disturbances . . . . The witness is our ability to watch the ego rather than identify with it.” (159). Not only does every single practice begin and end in stillness to observe, but I catch myself pausing throughout my day to simply observe and to witness. According to Adele, “self-study is about knowing our true identity as Divine and understanding the boxes we are wrapped in. This process of knowing ourselves, and the boxes that adorn us, creates a pathway to freedom.” (149). For me, Bhaktī reveals qualities that I have either discovered within myself or am still seeking to find, afterall, “We are, at the core, divine consciousness.” (149).

“We don’t see things as they are, we see things as we are.” – Anais Nin

Iśvara-Praṇidhāna, the final niyāma of Kriyā-Yoga, is surrending with humility and faith. According to Adele, “Surrender invites us to be active participants in life, totally present and fluid with each moment, while appreciating the magnitude and mystery of what we are participating in.” (166). There are an innumerable amount of unknown variables throughout my day-to-day life – a long list of “What ifs” . . . What if the weather or an accident affects my commute? What if I am in an accident? What if my students are “off the chain” today? What if my son is having a bad day? However, “Faith in the unknown can neutralize fear of the unknown.” (Buchman, 202). Referring back to the Yāmas, it requires us “To be strong enough to engage each moment with integrity and at the same time to be soft enough to flow with the current of life” (Adele, 172). Surrendering is by no means a passive act – it is a struggle that tests our integrity and requires an immense amount of courage (170). It also requires trust and faith in a divine force and acceptance “that whatever happens, happens.” (165, 204). For me, “Hanuman Bolo” immediately comes to mind in my daily “leaps” into the unknown.

The Third and Fourth Limbs

The Third and Fourth Limbs

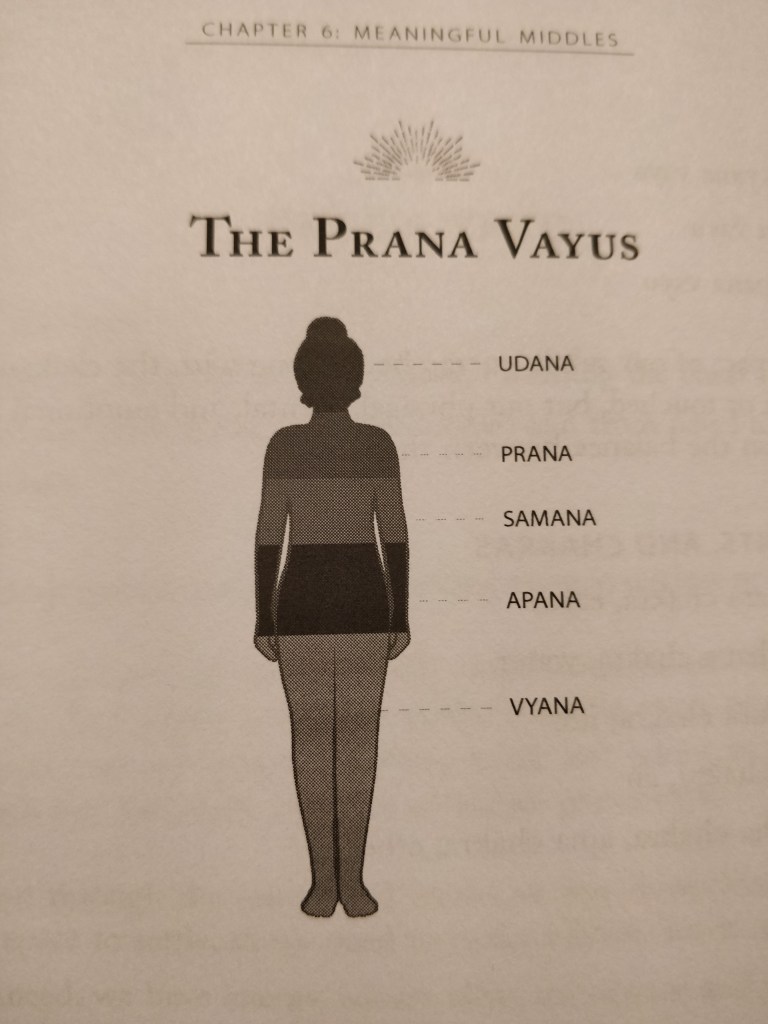

The third and fourth limbs entail one’s personal practice, to include Āsana and Prāṇāyāma. Āsana is the refinement of the body. Through physical practice, “impurities are churned up and released, allowing our life force (prāṇā) to flow more easily and improving our overall well-being.” (Bachman, 207). The physical practice also entails the regulation of breath, known as Prāṇāyāma since “Breath is a physical manifestation of prāṇā” (212). According to Bachman, “Prāṇāmoves everything in the body, including blood, lymph, nerve impulses, and ions. It also moves within our subtle energy points (marmas), energy channels (nādis), and energy centers (chakras).” (212). Thus, “Breathing exercises manipulate the prana and directly affect the body and the mind through the nervous system.” (213). Considering the importance and effects of prāṇāyāma, “The aim of Āsana is to reduce any hyperactivity in the nervous system” (208). In the early years of my yoga practice, it was purely about perfecting the postures and very little to do with my intuition or breathwork. Now, my practice focuses more on my breathwork and intuitively responding to what my body communicates to me in my physical practice.

The Fifth through Eighth Limbs

The fifth through eighth limbs concern one’s inner development known as Saṃyāma, inward concentration. Collectively, it is a means to move towards subtly and deeper the various layers of pre-conditioning. It begins with Pratyāhāra, the fifth limb, by tuning out sensory distractions where “we do not register sights, sounds, or other sensory details around us and are no longer distracted by external objects” (218). By tuning out our sensory distractions, “The true nature of our heart-mind is transparency, which allows out inner light of awareness to shine through our being without distortion and illuminate our world with knowledge, kindness, and compassion.” (219). With my attempts to find balance in my life, this continues to be a struggle for me, thus calming the mind chatter (chitta vritti) has always been a challenge for me. However, I have found that in my practice, I am able to gradually increase my ability to tune out distractions.

Saṃyāma progresses through to the sixth limb, Dhāraṇā, which Bachman defines as “keeping the attention on a single place” (227). Through the use of prāṇāyāma, we can draw our focus to one single point to help us to eliminate distractions; it entails becoming quiet, finding stillness, and acceptance of the present moment. Bachman suggests, “It is said in the Katha Upanishad (Kaṭhopaniṣad) that a flame the size of a thumb burns continuously in the heart, like a pilot light of life” (228). Janet’s guided meditation for Saṃyāma drawing attention to a focal point and allowing it to expand outward and then contract inward is something I will be incorporating to help me not only with the Pratyāhāra, but with maintaining that focus.

Saṃyāma progresses through to the sixth limb, Dhāraṇā, which Bachman defines as “keeping the attention on a single place” (227). Through the use of prāṇāyāma, we can draw our focus to one single point to help us to eliminate distractions; it entails becoming quiet, finding stillness, and acceptance of the present moment. Bachman suggests, “It is said in the Katha Upanishad (Kaṭhopaniṣad) that a flame the size of a thumb burns continuously in the heart, like a pilot light of life” (228). Janet’s guided meditation for Saṃyāma drawing attention to a focal point and allowing it to expand outward and then contract inward is something I will be incorporating to help me not only with the Pratyāhāra, but with maintaining that focus.

By extending the duration of focus leads us to the Seventh Limb, Dhyāna. According to Bachman, “Dhyāna blocks out the afflictive thoughts and emotions, allowing our heart-mind to absorb only the positive energy of the chosen object” (232). Here, one surrenders without any need to control and sets aside any pre-conditioning, and “If our chosen object is our heart, then we realize the same holds true for ourselves” (233). Once complete attention is attained, one enters the Eighth Limb known as Samādhi. Described as a spontaneous interaction with the here and now in complete and pure awareness, it becomes a realm of non-duality: “At this stage, there is no perception of a subject separate from its object.” (235).

“It is by going down into the abyss that we recover the treasures of life. Where you stumble, there lies your treasure.” – Joseph Campbell

As my reflection indicates, the long and arduous journey continues. Indeed, there is a lifetime of constructs and pre-conditionings that I need to work through. However, through these training sessions and my continued practice, the “boxes” reveal themselves, making me more mindful and aware. When I forget who I am, I will look deep within and remember.

Jaya Sita Rama, Jai Jai Hanuman 🙏

Works Cited:

Adele, Deborah. The Yamas & Niyamas: Exploring Yoga’s Ethical Practice. On-Word Bound: Duluth, 2009.

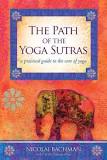

Bachman, Nicolai. The Path of the Yoga Sutras: a practical guide to the core of yoga. Sounds True: Boulder, 2011.

Nicolai Bachman’s

Nicolai Bachman’s  Each chapter covers a key concept, along with a relevant quote, analysis, thoughts and exercises for the practitioner. The author applies the principle to various modern examples and experiences, thus making it more accessible to the reader. For example, in Chapter 31 titled “Asteya” Bachman states, “If we interrupt someone during a conversation, we steal their right to be heard.” (154). According to Bachman, “The philosophy of yoga so eloquently written in these

Each chapter covers a key concept, along with a relevant quote, analysis, thoughts and exercises for the practitioner. The author applies the principle to various modern examples and experiences, thus making it more accessible to the reader. For example, in Chapter 31 titled “Asteya” Bachman states, “If we interrupt someone during a conversation, we steal their right to be heard.” (154). According to Bachman, “The philosophy of yoga so eloquently written in these